What does Earth Day mean to you? To me Earth Day is about the future, having a future, enjoying the future, creating a future in which we thrive.

I want to celebrate Earth Day 2013 by looking into the future. 2050 is attracting attention because trends reshaping civilization should converge about then. Some crystal ball gazers call it the great convergence. [1] According to my crystal ball, people living in 2050 will be:

- Wealthier and more urban,

- They will willing pay higher taxes, eat less meat, commute shorter distances, demanding less privacy, and live in smaller homes, and

- They will be stressed by greater air pollution, more water scarcity, and volatile price fluctuations in basic necessities like food

Before digging into the specifics about how my crystal ball works, I want to explain my purpose for sharing what I see. Quite simply, I want you to do something about the future. I want to make you more intentional, and thus more powerful at creating the future you want. Some of you may like parts of the future I described; others may hate all of it. Either way, the more you know what is coming, the more you can position yourself to make a difference and the more you believe you can make a difference, the more likely you are to act.

Game changing transitions in demographics, environment, governance, and markets are converging.

Demographic Transition: Urban Asian The first big trend is demographics, and we are familiar with the broad outlines of it. The human population will increase from 7 billion people living now to 9 billion people living in 2050 and then start to stabilize or even decline. The current US population is just over 300 million. So we will be adding 6 USAs between now and 2050.

Not only will there be more of us, we will be more wealthy. The great economic successes of China, Korea, India, Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia and other developing nations will continue if not accelerate as the driver of growth shifts from consumption by middle class living in the US and other G7 nations to the thriving global middle class. By 2050, the global economy could be 4 times what it is today, with estimates ranging from 2-6. This is good news. We might see an elimination of extreme poverty by 2030 (debilitating poverty of living on less than $2.50 dollars a day). There still will be poverty and inequity, but at least we are moving in the right direction. The plague of malnutrition will decline from 16% today to 5% by 2050. Just to give you one statistic to illustrate how fast things are improving, in Asia right now there are 500 million people enjoying middle-class lifestyles. By 2020 there will be 1.75 billion. History has never seen this kind massive betterment of so many people. While people in developed nations such as the US tend to be pessimistic about the state of the world, the rest of the world, the 88 percent who live outside the West, are actually saying, “We have never had better times in our history.”[2] By 2050 three billion more people will move into the global middle class, demanding political stability, a better future for children, accountability and transparency by governments and companies, and the rule of law.

Not only will there be more of us, and more wealth, we will also be more urban. 98% of the population growth will occur in cities: 1 million people per week. And most of those cities will be in Asia. Hence the motto for the demographic transition: urban Asia. Proximity has mattered since the dawn of time. We are social creatures and migrate to cities seeking safety, wealth, status, sex and opportunity. The US is now at least 70% urban, by 2050 the rest of the world will be too. In 1900 there were about 1.7 billion people, 10% urban (the US was already 50% urban). By 2000 the human population was 6B and the world became 50% urban. By 2050 we will be at 9 billion with 70% of us urban.

Amazingly that means we will need to double the amount of infrastructure and built urban environment. That is, we will double everything built between time 0 and now. Fortunately we know how to do it right, with smart growth principles, green infrastructure, and green buildings. Most importantly, urbanization is a good thing for sustainable development. Urbanites makes more money than comparably educated ruralites doing essentially the same job. States and nations with more urbanization have less poverty. Urbanites also commute less, consume less energy per person, and live in small homes. Cities are where the battle for sustainable development will be won or lost (see E Glasser, Triumph of the City).

Governance Transition: Collaboration The transition occurring in governance should be obvious and familiar. You can see it with your own eyes. Confidence in Congress is at all time low. Elections have become a time to throw the bums out. National debt is mounting. Municipalities are going bankrupt and defaulting on bonds. Voters seem tax-intolerant yet demand more health, welfare, education and basic social systems. Government is being starved and delegitimized, perhaps intentionally.[3] Add to these trends the public’s loss of confidence in science and technology, and in experts generally, evidenced by debates over evolution and climate change as well as charges of conspiracy among scientists and bureaucrats. None of this bodes well for government, whose actions and policies require investment of public money legitimized by rational, science-heavy, techno-centric logic.

In addition, nation-states are struggling to keep up with the demands of the global economy. They are unable to manage what crosses their borders: goods and services circle the world in long complex supply chains, pollution travels through air and water that know no political boundaries and in or on goods we all consume. Labor may not be exploited in our communities, but it may be in the ones that manufacture our clothes and electronics. Public health epidemics, such as the latest variants of bird and swine flu can spread around the globe as fast as people travel.

Multinational corporations and larger than most governments. Of the 100 largest economic entities in the world, ½ are companies. Wal-Mart’s economic capacity is larger all but the top 20 countries. General Electric is bigger than New Zealand. Amazon is bigger than Kenya. Public Infrastructure—the bread and butter of government– is being privatized, owned and managed by corporations: highways, ports, and airports…even the Panama Canal. Thirty corporations today control 90% of world internet traffic. Even national defense is being privatized.

In the face of all this: some of the most powerful forces for change are occurring through collaboration in the cross-sector space: where business, government, civil society overlap. Governments use law and regulation to level the playing field, prevent a race to the bottom, establish markets, and make sure good actors don’t get punished and bad do. Corporations have money and management capacity and motivations for risk reduction. NGOs have moral authority, but perhaps most importantly can look problems outside temporal and spatial limits of business and politics (quarterly profits, election cycles, political boundaries, market jurisdiction).

Environmental Transition: The Anthropocene. We can’t discuss Earth Day without delving into the “environment.” The environmental impacts of human civilization are well documented, and I will list notable statistics here. But, the story is more compelling if we start 12,000 or so years ago, when the current geological age began: the Holocene, an era of relative climate, geologic, and ecological stability, and an era when humans mastered agriculture and science and spread civilization around the globe. Today, humans have become a dominant force, a partner to evolution in the fate of Earth, and thus we live in a new geological period—the Anthropocene. Every system and species on Earth are now linked to humanity. A cursory internet search of “Planetary Boundaries,” “Ecological Footprint,” “State of the World” or “limits of growth” provides a litany of environmental challenges. This familiar chorus of alarms has been joined by new voices such as the National Intelligence Council, OECD, WBSCD, PriceWaterhouseCooper, McKinnsey Consulting, and KMPG.

Indicators of human biosphere dominance confirm that we now live in the Anthropocene. The fundamental ecological services that support us with food, water and oxygen are now ours to manage.

- Climate: 80% of the GHG emissions needed to cause 2 degrees of warming are already built into our electricity and transportation system. That is, we will find it fiscally and politically challenging to retire before we’ve paid off existing investments in new or relatively new coal fired electricity generation plants, fleets of petroleum powered vehicles, and cities full of hot water and air conditioning buildings powered by natural gas. We probably already are in the era of climate adaptation; by 2050 we certainly will be living with wetter wets, colder colds, dryer drys, hotter hots, and eroding coastlines.

- Nitrogen: We now fix and use much more nitrogen than all other parts of the biosphere combined. In 1909, Fritz Haber figured out how to fix nitrogen from thin air and launched a fertilizer industry that fueled the green revolution and possibly fanned the human population explosion. Nitrogen runoff from fertilizer used on US farms produce a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico roughly the size of New Jersey. Few inventions have been more transformative.

- Land area: The following numbers are approximations and vary depending on definitions used, but: 10 percent of Earth’s land is paved or built upon; 40 percent is used for crops or livestock; 20% is rocks, ice, and marsh unsuitable for “production;” 30% is forested, way more than half of which is managed for timber and toilet paper and the remainder is designated as protected areas or public lands.

- Water: Water tables around the world are dropping: Mexico 6 feet a year, Iran 10 feet a year, China and India perhaps even more. The decline of the Ogallala Aquifer, which irrigates America’s breadbasket, is alarming. Saudi Arabia ceased growing wheat because it lacked water. China’s now imports most of its soybeans because it doesn’t have the water to grow them. Irrigation for agriculture claims 70 percent of the freshwater withdrawals worldwide (and agricultural production might need to double by 2050 to meet needs of more wealthy, meat eaters). While water pollution may be decreasing worldwide, water stress is increasing. As many as 50% of people will be living in water stressed areas by 2050.

- Biodiversity is declining at a rate that eclipses the great extinction events of the past.

- Air pollution is increasing and will be the # 1 environmental related cause of early death by 2050. The primary pollutants will be the soot, mercury, and ground level ozone resulting from fossil fuel combustion. They cause asthma and other respiratory diseases.

- Ocean Fisheries: Over 20% of ocean fisheries have collapsed, another 30% are being exploited above their sustain yield and may collapse. Most of the remaining fisheries are healthy but are being harvested at our near their sustained yield. Few untapped fisheries exist.

- Trash Islands: Plastic bags, water bottles, and other disposable plastics not only create mountains of waste, they float. More tiny particles of plastic float in the ocean than plankton. Water currents in the Pacific create trash islands the size of Texas.

- Malthusian Scarcity: Paul Ehrlich placed is famous bet with Julian Simon too soon. He lost his wager that the price of key commodities would increase because of increasing scarcity. Instead, prices fell as they had for the previous decades and continued falling until about the year 2000. Since then, spikes and volatile have erased a century of steadily declining prices,[4] motivating the market transition, discussed below.

Market Transition: Green Economy. If asked to identify the drivers behind the emerging “green” economy, most people would say: “I don’t know or care.” Those who do know and care assume that consumer driven demand for green products will transform industry. They argue that suppliers of consumer goods and services will respond to demand in the marketplace for products labeled natural, sustainable, FSC, MSC, fair trade, energy star, recycled, organic, and local. They would be wrong. These purchases have minimal impacts on sustainability. First, consumers don’t have enough time to process all the information the labels convey: just think how overwhelmed you would be trying to master the labels in the grocery story aisle full of cereal. Second, even if you understand what a label means, most of us won’t pay a price premium, so there is not an incentive to produce it. Third, people just aren’t rational: we don’t even buy stuff we know saves us money, like insulation. And, finally, labels and green marketing perpetuate materialism and consumerism—i.e., we just buy more stuff. OK, I’ll back off. Product certification and labeling have a host of positive spinoff consequences, but they certainly are not game changers.[5]

Other demand-side decisions might be more consequential. Institutional buyers, for example, can jumpstart new product lines: schools authorities and government agencies can require that new buildings be LEED certificated, that all copier paper be FSC certified, and all tomatoes organic. Boycotts are also drivers of market change. Social media interconnectivity and a 24-hour news cycle can create brand damaging public relations fiascos if a company finds itself on the wrong side of an environmental disaster, threat to public health, or labor practices deemed unfair. Threats to damage a company’s brand are taken seriously and have transformed whole companies, examples include dolphin safe tuna, humanely slaughtered beef, and running shoes made without child labor.

But risk management is the real driver behind the emerging green economy. It turns out that sustainability is a key to profitability because those long, taut supply chains stretching several times around the globe are vulnerable to resource scarcities, price fluctuations, climate change, and social disruption. Businesses are waking up to the 2050 trends and integrating resource scarcity and climate risks into their management practices.[6]

There is nothing new about businesses managing supply chains to minimize costs and risks. Profits increase with declining costs for inputs of materials, energy, and labor, as well as declining costs of waste processing and disposal. Technological innovation and product re-design have been decoupling profits from material inputs since the industrial revolution began. The holly grail (for both business and for sustainable development) is a cradle-to-cradle product design-manufacture-use-recycle system that redirects product disposal back into production of new goods and services, giving businesses complete control over manufacturing inputs and risks while eliminating expensive waste and liabilities. As the price volatility and supply reliability risks increase for resource inputs, so do motivations to recycle, reduce, and reuse.

Several years ago confectionery giants Kraft and Sara Lee, for example, were unable to buy sugar because of global shortages and had to shut down production facilities, or if they could get sugar, the high prices reduced overall profitability by 10–20 percent. Similarly, a few years back, climate chaos impeded the ability of giant food distributors to secure tomatoes from regular suppliers in Florida because of an early frost, from secondary suppliers in California because of drought, and back up suppliers in Mexico because of flooding. So companies bought much more expensive hothouses tomatoes, making the hard choice to sacrifice profits rather than risk not being able to satisfy consumer demand. Consequently, companies have begun to manage consumer demand, directing that demand towards the goods and services companies can reliably provide at the time and place consumers want and at a price they can afford. “Choice editing” (advertising) that redirects consumer preferences increasing reflect corporate sustainability concerns.[7]

Visualize an hourglass, with 10 billion retail consumers representing a very wide base and millions of producers of energy, water, corn, cotton, and other resources and commodities representing the top. The narrow middle represents several thousand multinational corporations with long supply chains reaching from natural capital through the means of production, packaging, transport, and marketing all the way to retail consumers. These MNCs influence 40-70% of all production in some markets and thus can have huge impacts on humanity’s sustainable development trajectory. Green supply chains may be the white knights of sustainable development.[8] NGOs and governments have been focusing enormous attention on the neck of the hourglass in hopes that establishing norms for sustainable and profitable business practices among the top corporations will flip whole industries into sustainable consumption and production (WBCSD, EDF, WWF, TNC)

A raft of other powerful motivations exists for businesses to practice sustainable consumption and production.[9] Investors and insurers are increasingly cautious of risky and unsustainable practices.[10] Better employee recruitment and retention provides another motive for businesses to align themselves with the sustainable consumption strategy. Employees consider a company’s sustainability efforts during the job search, so businesses with meaningful CSR programs attract and retain higher quality employees.[11]

Supply chain efficiencies and demand-side management will be necessary but probably not sufficient for sustainable development, certainly not until and unless the cost of environmental and social externalities are incorporated into the prices paid for resources and the accounting systems used to evaluate “development.” The market is an amazing algorithm for efficiently allocating time and resources, the best we have. But because so many externalities exist, the market is making poor decisions. The largest 3,000 companies in the world, failed to account for approximately US$2.15 trillion worth of pollution, waste, and degradations to natural systems — 3.6% of global GDP. [12] Structural fixes to the economy such as privatization and cap-and-trade are essential strategies for sustainable development.

Thus, the greening of our economy must be led by collaboration among governments, NGOs, and companies, not by consumers. Individuals don’t have the management capacity to make informed choices about which goods and services are sustainable: there is too much to know, too little time and resources to know it, and too little control over the means of production. Green Certification and Good Guides will help steer the market, but not drive the change we need. We can’t buy our way out of our dilemma, but we can manage our way to a better 2050 and beyond.

Building capacity to respond

These trends should all converge around 2050: hence the title of this essay. The time between now and then will be full of opportunities and challenges for humanity, and you in particular. How should you respond? How should you prepare?

To help think through the opportunities and challenges, I want to use a nautical analogy: Imagine in your minds eye the task of navigating a vast ocean.[13] Up until the recent past, all nations, cities, businesses, NGOs, churches, charities and schools were like ships making their own way on the open seas: setting their own courses, solving their own problems, suffering their own fates. Now all those ships are tied together by globalization and by the Anthropocene: millions of ships tied together, some loosely, some tightly; millions of captains, first mates, mechanics, and custodians; millions of strategies for navigating, provisioning, and disposing of wastes. In this new world, where should you be building capacities that position you to have meaningful influence? I have five suggestions.

First, we need to understand the ocean currents, prevailing winds, and other forces that affect navigation so we can steer our ships around the challenges and towards opportunities. The 4 big transitions are a map that aids navigation. Transitions in demographics, environment, markets, and governance are creating shoals upon which ships can founder, headwinds that can’t be overcome, and currents that will take us to safe harbor. If you see these trends and transitions, you are better positioned to respond to them. So one thing to do is read up on 2050 transitions.

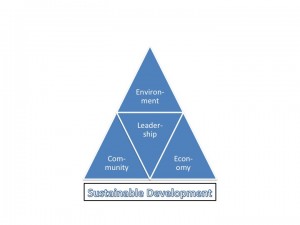

Second, we need to collaborate. We need a different model of leadership. We can’t all expect to steer, maintain, and provision ours ships as we have in the past. The institutions of the 20th century are not equipped to solve the 21st century challenges. Disciplines and professions remain powerful, but solutions require team-based collaboration and innovation, working across disciplinary and professional boundaries, paridigms, and mindsets. We also need to collaborate across the boundaries that exist within the large, global, complex organizations. Organizational change for sustainable development requires new organizational structure and leadership. As importantly, collaborations must occur across organizations working in different sectors. No organization, or no sector, can solve the challenges of poverty, climate change, fisheries collapse, or public health epidemics. Cross- sectors, multi-stakeholder collaborative efforts will be required. Businesses, government agencies and civil society organizations must increasingly partner with one another, each bring needed insights, motivations, skills can capacities.

Third, we need more, better and different technical experts. Many of the 21st century challenges will be solved with expertise and innovation. What expertise will be in demand? Where should you focus your education and practice to become more influential and consequential? Look at the transitions. The demographic transition suggests much of the action will be in Asia, so one obvious implication is to gain language skills, international experiences, and build networks that make you effective there. Massive urbanization, another facet of the demographic transition, suggests tremendous opportunity for experts in green infrastructure, smart buildings, and smart growth. Mushrooming consumer demand points to stress points in agriculture, water, and energy production. Whole new systems need to be invented and applied. Another tremendous growth opportunity exists at the confluence of business administration, public administration, and environmental science. Business schools are already incorporating sustainability issues into their curricula, but they still lack a solid grounding in the complex environmental systems that ultimately determine the risks to supply chains that managers are trying to control. Public administrators and managers of social benefit organizations likewise need to better integrate environmental systems thinking into their theories and practices. Most importantly, the rather insular environmental sciences need to expand or redirect their focus from solving environmental problems and studying environmental systems to solving sustainable development challenges and studying bio-cultural systems.

Fourth, we need to scale up solutions from local successes to regional, national, and global practices. We face a pace of change greater than we have experienced at any point in humanity. The great convergence really is humanity’s defining moment. We will need to bring online countless innovations, many of which already exist but are not yet scaled up. Learning-networks, communities-of-practice, collective-impact, scaling-up, and similar technologies will be critical for implementing lessons learned and mentoring others in applications of promising and proven solutions.

Finally, we need to be willing to fail. We need to overcome the intolerance and polarization that so polarizes our politics. We need to accept that we will get things wrong. Government programs will be ineffectual or misdirected. Business investments, and government subsidies in them, will falter. NGOs will be misdirected. Good. We need more of it. More experiments. More humility. The humility prepares us to fail and learn from the failure. It gives us license to try again. And again. Each time monitoring our efforts, so we can re-adjust our methods and goals, adapt, and, yes, try again. We must experiment. Experimentation is the basis of adaptive management, and adaptive management is the key to living in adaptive systems—the systems that will define 2050. We must overcome our political intolerance for trial and failure. We need to celebrate failure and learning by doing. Pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The great convergence is coming. Getting through it will require overcoming enormous challenges, but the future we create can be a place where more and more people thrive. (and some biodiversity too!) We need to get busy creating that future. The solutions and tools are within reach. If we willingly, intentionally engage in creating our future, and do so with courage and humility, then that future will be wonderful. Let’ get busy. Earth Day is about the future. Celebrate Earth Day everyday.

**(I presented a version of this blog at Univeristy of Illinois at Springfield in celebration of Earth Day 2013. A recording of the talk is available. Visit the Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability, where I work with colleagues promoting leadership for a better future)

FOOTNOTES

[1] Michael Spence’s “The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World. Kishore Mahbubani’s “The Great Convergence”

[2] Kishore Mahbubani the great convergence

[3] Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein. It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism.

6. e.g., McKinsey&Company Resource Revolution

[13] Analogy adapted from Kishore Mahbubani’s The Great Convergence.